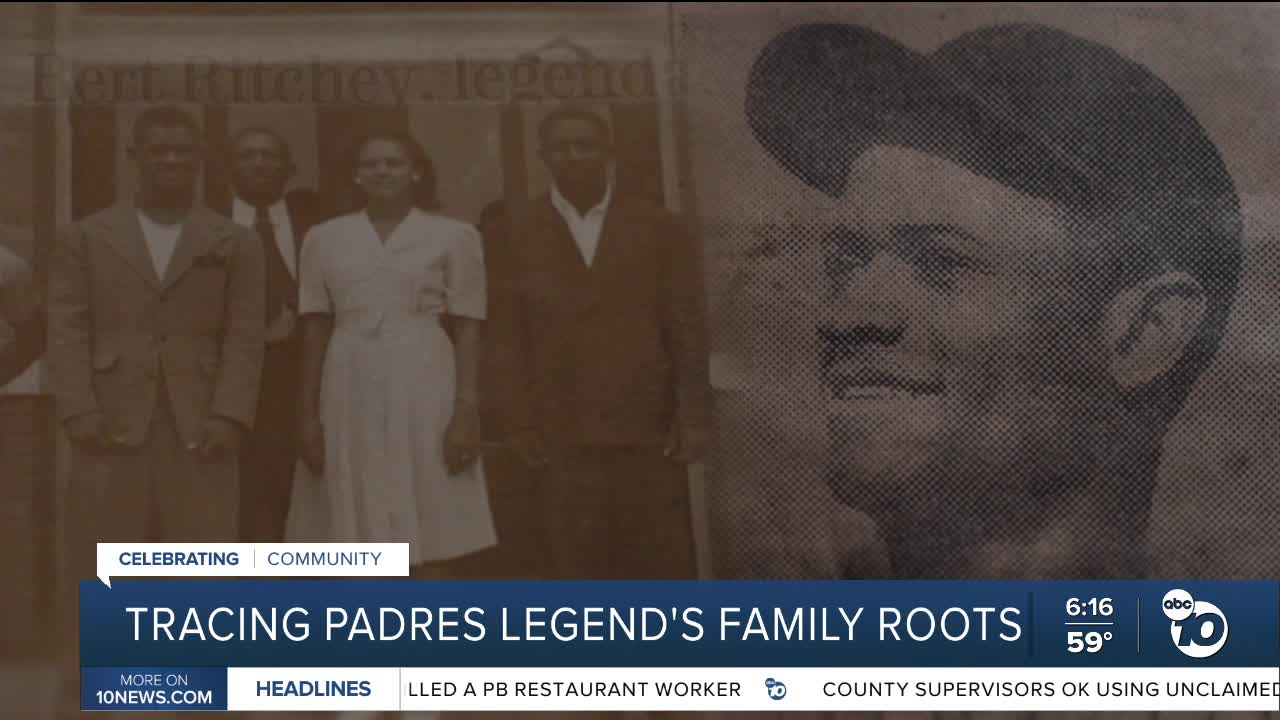

SAN DIEGO (KGTV) — A genealogist's research has uncovered the remarkable ancestry of Johnny Ritchey, the first Black man to play for the San Diego Padres, revealing his family's deep roots in San Diego County dating back to the 1890s.

The discovery came as part of a decades-long search by Ritchey's family members to trace their lineage, working with genealogist Yvette Porter Moore to uncover their historical connections.

"I was pulled into do a little more research on Johnny Ritchie's ancestry, and so that meant looking deeply into when the family started arriving in San Diego," Porter Moore said.

The research revealed that Ritchey's story begins with his great-great-grandparents, Thomas Debose and Christina Moss, who were born in the 1840s in Virginia during slavery.

"I've been looking into Johnny Richie's family, the Richie family, and from what I have discovered that it begins with the Debose and Moss family, so Christine Moss and Thomas Debose," Porter Moore said.

Porter Moore's first task was determining whether Thomas was born free or enslaved. Before 1870, only free Black Americans appeared on census records, while enslaved people were listed on slave schedules that only showed slave owners' names and the number of people they owned.

The research showed Thomas Debose was listed in the 1860 census records, indicating he was free.

"It makes me feel good. It makes me feel powerful. Or equal," said Ed Fletcher, Johnny Ritchey's second cousin.

Records from January 10, 1866, show Thomas was an indentured servant to Thomas Warren. The documents indicate he was 11 years old and an orphan.

"I was thinking that they may have given him the wrong age because it would be advantageous for them to give him the wrong age so that they could keep him in servitude up to the age of 21," Porter Moore said.

The indenture agreement stated Thomas would be taught to read, write, and learn farming. Upon completion, he would receive $50 and a freedom suit – new clothes symbolizing the transition from bonded labor to free-working class status.

"I didn't know any of this," said Antonette Gordon, Johnny Ritchey's third cousin.

Fletcher added that while he knew his grandfather William Ritchie was an orphan, he didn't know Thomas was also an orphan.

Thomas and Christina lived in Virginia, Illinois, and Ohio before settling in San Diego County in 1892. Thomas bought at least eight lots in La Jolla and operated horse stables on the property where the Bishop's School now stands.

"They came to La Jolla in 189,2 and Thomas Dubose bought property, at least 8 lots at that time, and he trained horses before he came to La Jolla, and he had stables on one of his lots, which is where the bishop's school is built now," Gordon said.

The Debose family became one of the first Black families to buy land in La Jolla.

"I was just proud of that, since he owned the property first," Gordon said.

Thomas and Christina had six children and 14 grandchildren, including Johnny Ritchey, who would later break barriers as the first Black player for the San Diego Padres.

"I was just a little girl, but we would be at every ball game, and we were so proud to see him catching and being a relative, so we enjoyed him," Gordon said.

Fletcher remembered being amazed by the respect Ritchey commanded.

"I can remember his just being amazed that he was so held in such awe," Fletcher said.

However, like many Black Americans researching their ancestry, the family's search stops at Thomas Debose and Christina Moss, leaving more questions than answers.

"I think we're just barely touching the surface. I think we've got to learn a lot more, and I'd like to know a lot more about my family and I'd like to go back as far as I can go," Fletcher said.

Johnny's daughter, Johnna Ritchey-Battle, shares that sentiment.

"I don't know if we'll ever really be able to trace the very beginning of our ancestry. So that kind of saddens me a little bit," Ritchey-Battle said.

When asked what her father would think about these discoveries, she said he would be proud.

"They would be proud, my dad and all the others to know that because of modern technology, we're able to go back in history and find out who we really are," Ritchey-Battle said.

The family plans to preserve this history in a book for future generations. The genealogist says the next steps include DNA testing and traveling to Virginia to retrieve documents that can only be obtained in person.

This story was reported on-air by a journalist and has been converted to this platform with the assistance of AI. Our editorial team verifies all reporting on all platforms for fairness and accuracy.